Tropic of Cancer Henry Miller Read Online

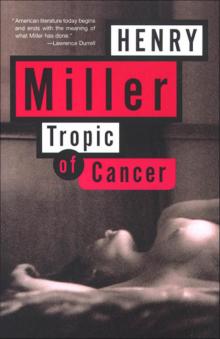

Tropic of Cancer

These novels will requite fashion, by and by, to diaries or autobiographies—captivating books, if but a man knew how to choose among what he calls his experiences that which is really his experience, and how to tape truth truly.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

HENRY MILLER

Tropic of Cancer

Introduction by Karl Shapiro Preface by Anaïs Nin

Copyright © 1961 past Grove Press, Inc.

All rights reserved. No office of this book may be reproduced in whatsoever form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including data storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy role or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an album, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Textile quoted in the Introduction from other works by Henry Miller is reprinted by the kind permission of New Directions: Wisdom of the Heart, copyright © 1941 by New Directions; The Smile at the Pes of the Ladder, copyright © 1948 by Henry Miller; The Fourth dimension of the Assassins, copyright © 1946, 1949, 1956 by New Directions.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Information

Miller, Henry, 1891-1980

Tropic of Cancer. New York, Grove Press [1961]

318 p.

I. Title.

PS3525.I5454T7 1961 818.52 61-15597

ISBN-10: 0-8021-3178-vi

ISBN-xiii: 978-0-8021-3178-ii

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group W

www.groveatlantic.com

09 10 40 39 38

The Greatest Living Author*

I call Henry Miller the greatest living author because I think he is. I do non phone call him a poet considering he has never written a poem; he even dislikes poetry, I think. Merely everything he has written is a poem in the best as well as in the broadest sense of the discussion. Secondly, I do not call him a writer, but an author. The writer is the wing in the ointment of mod letters; Miller has waged ceaseless state of war confronting writers. If one had to blazon him one might call him a Wisdom writer, Wisdom literature being a type of literature which lies betwixt literature and scripture; it is poetry only because it rises above literature and considering information technology sometimes ends upwardly in bibles. I wrote to the British poet and novelist Lawrence Durrell last twelvemonth and said: Let's put together a bible of Miller's work. (I idea I was existence original in calling it a bible.) Let'south assemble a bible from his piece of work, I said, and put 1 in every hotel room in America, after removing the Gideon Bibles and placing them in the laundry chutes. Durrell, notwithstanding, had been working on this "bible" for years; I was a Johnny-come up-lately. In fact, a group of writers all over the world accept been working on it, and one version has at present come out.

In that location was a commonplace reason why this book was very much needed. The author'due south books accept been almost impossible to obtain; the ones that were non banned were stolen from libraries everywhere. Even a copy of 1 of the nonbanned books was recently stolen from the mails en road to me. Whoever got it had better be a book lover, because information technology was a bibliography.

I will introduce Miller with a quotation from the Tropic of Cancer: "I sometimes inquire myself how information technology happens that I concenter cypher just crackbrained individuals, neurasthenics, neurotics, psychopaths—and Jews peculiarly. There must be something in a good for you Gentile that excites the Jewish listen, similar when he sees sour blackness staff of life." The "healthy Gentile" is a good sobriquet for Miller, who unremarkably refers to himself equally the Happy Rock, Caliban, "just a Brooklyn boy," "Someone who has gone off the gold standard of Literature" or—the name I similar all-time—the Patagonian. What is a Patagonian? I don't know, but it is certainly something rare and sui generis. We can telephone call Miller the greatest living Patagonian.

How is one to talk nearly Miller? At that place are authors 1 cannot write a volume or even a good essay nigh. Arthur Rimbaud is ane (and Miller's book on Rimbaud is one of the best books on Rimbaud ever written, although it is mostly about Henry Miller). D. H. Lawrence is another writer one cannot comprehend in a volume "well-nigh" (Miller abandoned his volume on Lawrence). And Miller himself is one of those Patagonian authors who just won't fit into a book. Every give-and-take he has ever written is autobiographical, but only in the way Leaves of Grass is autobiographical. There is not a give-and-take of "confession" in Miller. His amorous exploits are sometimes read as a kind of Brooklyn Casanova or male Fanny Hill, simply there is probably not a word of exaggeration or boasting to speak of—or simply as much equally the occasion would call for. The reader tin can and cannot reconstruct the Life of Henry Miller from his books, for Miller never sticks to the subject area whatsoever more than Lawrence does. The fact is that at that place isn't any subject and Miller is its poet. Merely a little information about him might help present him to those who need an introduction. For myself, I do not read him consecutively; I choose one of his books blindly and open it at random. I have just washed this; for an instance, I discover: "Man is non at habitation in the universe, despite all the efforts of philosophers and metaphysicians to provide a soothing syrup. Thought is all the same a narcotic. The deepest question is why. And it is a forbidden one. The very asking is in the nature of cosmic sabotage. And the penalty is—the afflictions of Job." Not the greatest prose probably, but Miller is not a writer; Henry James is a writer. Miller is a talker, a street corner gabbler, a prophet, and a Patagonian.

What are the facts about Miller? I'thou not sure how important they are. He was born in Brooklyn near 1890, of German beginnings, and in sure means he is quite German. I take ofttimes idea that the Germans brand the best Americans, though they certainly make the worst Germans. Miller understands the German in himself and in America. He compares Whitman and Goethe: "In Whitman the whole American scene comes to life, her past and her future, her birth and her death. Whatever there is of value in America Whitman has expressed, and there is nothing more to be said. The future belongs to the machine, to the robots. He was the Poet of the Body and the Soul, Whitman. The first and the last poet. He is almost undecipherable today, a monument covered with rude hieroglyphs, for which in that location is no central. … At that place is no equivalent in the languages of Europe for the spirit which he immortalized. Europe is saturated with fine art and her soil is full of dead basic and her museums are bursting with plundered treasures, just what Europe has never had is a free, healthy spirit, what you might call a MAN. Goethe was the nearest approach, merely Goethe was a stuffed shirt, by comparing. Goethe was a respectable denizen, a pedant, a diameter, a universal spirit, just stamped with the High german trademark, with the double eagle. The serenity of Goethe, the calm, Olympian attitude, is nothing more than the drowsy stupor of a German bourgeois deity. Goethe is an end of something, Whitman is a beginning."

If everyone tin decipher the Whitman central information technology is Miller. Miller is the twentieth-century reincarnation of Whitman. But to return to the "facts." The Brooklyn Boy went to a Brooklyn high school in a day when most high schools kept higher standards than near American universities today. He started at CCNY just quit almost immediately and went to work for a cement company ("Everlasting Cement"), then for a telegraph visitor, where he became the personnel manager in the biggest city in the world. The telegraph company is chosen the Cosmodemonic Telegraph Company in Miller'south books, or in moments of gaiety the Cosmococcic Telegraph Company. One solar day while the vice-president was bawling him out he mentioned to Miller that he would like to come across someone write a

sort of Horatio Alger book about the messengers.

I idea to myself [said Miller]—y'all poor erstwhile futzer, yous, merely wait until I go it off my chest. … I'll requite you an Horatio Alger volume. … My head was in a whirl to go out his office. I saw the army of men, women and children that had passed through my easily, saw them weeping, begging, beseeching, imploring, blasphemous, spitting, fuming, threatening. I saw the tracks they left on the highways, lying on the floor of freight trains, the parents in rags, the coal box empty, the sink running over, the walls sweating and between the cold chaplet of sweat the cockroaches running like mad; I saw them hobbling forth like twisted gnomes or falling backwards in the epileptic frenzy. … I saw the walls giving way and the pest pouring out like a winged fluid, and the men higher upwards with their ironclad logic, waiting for it to blow over, waiting for everything to be patched up, waiting, waiting contentedly… proverb that things were temporarily out of order. I saw the Horatio Alger hero, the dream of a sick America, mounting college and college, offset messenger, then operator, so manager, then primary, then superintendent, then vice-president, then president, so trust magnate, then beer businesswoman, then Lord of all the Americas, the money god, the god of gods, the clay of clay, nullity on high, goose egg with ninety-seven thou decimals fore and aft. … I will give you Horatio Alger as he looks the day after the Apocalypse, when all the stink has cleared away.

And he did. Miller's get-go volume, Tropic of Cancer, was published in Paris in 1934 and was immediately famous and immediately banned in all English-speaking countries. It is the Horatio Alger story with a vengeance. Miller had walked out of the Cosmodemonic Telegraph Visitor one mean solar day without a word; ever after he lived on his wits. He had managed to get to Paris on ten dollars, where he lived more than a decade, not during the gay prosperous twenties but during the Great Depression. He starved, fabricated friends by the score, mastered the French language and his ain. Information technology was not until the Second World War bankrupt out that he returned to America to live at Big Sur, California. Among his best books several were banned: the two Tropics (Tropic of Cancer, 1934, and Tropic of Capricorn, 1939); Black Spring, 1936; and part of the trilogy The Rosy Crucifixion (including Sexus, Plexus, and Nexus).

Unfortunately for Miller he has been a man without award in his own country and in his ain language. When Tropic of Cancer was published he was even denied entrance into England, held over in custody by the port authorities and returned to France by the next boat. He made friends with his jailer and wrote a charming essay about him. Only Miller has no sense of despair. At the first of Tropic of Cancer he writes: "I take no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive."

George Orwell was one of the few English critics who saw his worth, though (mirabile dictu) T. S. Eliot and even Ezra Pound complimented him. Pound in his usual ungracious manner gave the Tropic of Cancer to a friend who later on became Miller's publisher, and said: Hither is a dirty book worth reading. Pound even went and so far every bit to try to enlist Miller in his economic system to save the world. Miller retaliated by writing a satire called Money and How Information technology Gets That Way, dedicated to Ezra Pound. The acquaintanceship halted there, Miller'due south view of coin being something like this (from Tropic of Capricorn): "To walk in coin through the night crowd, protected by coin, lulled past money, dulled by money, the crowd itself a money, the jiff money, no least single object anywhere that is not money, money, coin everywhere and however not plenty, then no money, or a little money or less coin or more money, but money, always money, and if you have money or you don't take money it is the money that counts and money makes money, simply what makes money make money?" Pound didn't intendance for that brand of economics.

But all the writers jostled each other to welcome Miller amidst the elect, for the moment at to the lowest degree: Eliot, Herbert Read, Aldous Huxley, John Dos Passos and amongst them some who really knew how good Miller was: William Carlos Williams, who chosen him the Dean, Lawrence Durrell, Paul Rosenfeld, Wallace Fowlie, Osbert Sitwell, Kenneth Patchen, many painters (Miller is a fanatical water colorist). But mostly he is beset by his neurasthenics and psychopaths, every bit whatsoever cosmodemonic poet must exist. People of all sexes oft turn up at Big Sur and announce that they desire to join the Sex activity Cult. Miller gives them coach fare and a adept dinner and sends them on their way.

Orwell has written i of the all-time essays on Miller, although he takes a sociological approach and tries to identify Miller as a Depression author or something of the sort. What astonished Orwell about Miller was the difference between his view and the existential bitterness of a novelist like Céline. Céline's Voyage au bout de la Nuit describes the meaninglessness of modern life and is thus a prototype of twentieth-century fiction. Orwell calls Céline'due south book a cry of unbearable disgust, a voice from the cesspool. And Orwell adds that the Tropic of Cancer is almost exactly the opposite! Such a thing as Miller's volume "has become and then unusual as to seem almost anomalous, [for] information technology is the book of a human who is happy." Miller also reached the lesser of the pit, equally many writers do; merely how, Orwell asks, could he have emerged unembittered, whole, laughing with joy? "Exactly the aspects of life that fill Céline with horror are the ones that appeal to him. So far from protesting, he is accepting. And the very word 'acceptance' calls upwardly his existent affinity, another American, Walt Whitman."

This is, indeed, the crux of the matter and information technology is unfortunate that Orwell cannot see by the socio-economic situation with Whitman and Miller. Notwithstanding, this English language critic recognizes Miller'southward mastery of his material and places him among the neat writers of our age; more than that, he predicts that Miller will set up the pace and attitude for the novelist of the futurity. This has non happened withal, but I agree that information technology must. Miller'south influence today is primarily among poets; those poets who follow Whitman must necessarily follow Miller, even to the extent of giving up poesy in its formal sense and writing that personal apocalyptic prose which Miller does. It is the prose of the Bible of Hell that Blake talked about and Arthur Rimbaud wrote a chapter of.

What is this "acceptance" Orwell mentions in regard to Whitman and Henry Miller? On ane level it is the poetry of catholic consciousness, and on the most obvious level it is the verse of the Romantic nineteenth century. Miller is unknown in this land because he represents the Continental rather than the English influence. He breaks with the English literary tradition merely as many of the twentieth-century Americans do, because his beginnings is not British, and not American colonial. He does not read the favored British writers, Milton, Marlowe, Pope, Donne. He reads what his grandparents knew was in the air when Victorianism was the genius of British poetry. He grew up with books past Dostoevski, Knut Hamsun, Strindberg, Nietzsche (especially Nietzsche), Élie Faure, Spengler. Similar a true poet he institute his way to Rimbaud, Ramakrishna, Blavatsky, Huysmans, Count Keyserling, Prince Kropotkin, Lao-tse, Nostradamus, Petronius, Rabelais, Suzuki, Zen philosophy, Van Gogh. And in English he allow himself be influenced not by the solid classics but by Alice in Wonderland, Chesterton's St. Francis, Conrad, Cooper, Emerson, Rider Haggard, G. A. Henty (the boy'south historian—I remember existence told when I was a boy that Henty had the facts all wrong), Joyce, Arthur Machen, Mencken, John Cowper Powys, Herbert Spencer'southward Autobiography, Thoreau on Ceremonious Disobedience, Emma Goldman—the great anarchist (whom he met)—Whitman, of form, and mayhap above all that companion piece to Leaves of Grass called Huckleberry Finn. Hardly a Peachy Books listing from the shores of Lake Michigan—almost a period list. Miller will introduce his readers to foreign masterpieces similar Doughty's Arabia Deserta or to the periodical of Anaïs Nin which has never been published simply which he (and other writers) swears is ane of the masterpieces of the twentieth century. I imagine that Miller has read as much as any homo living merely he does non have that religious solemnity about books which we are brought upwardly in. Books, after all, are just mnemonic devices; and poets are always celebrating the burning of libraries. And as with libraries, so with monuments, and as with monuments, so with civilizations. Just in Miller's case (chez Miller) in that location is no vindictiveness, no bi

tterness. Orwell was bothered when he met Miller because Miller didn't want to go to the Castilian Civil War and do battle on one side or the other. Miller is an anarchist of sorts, and he doesn't specially intendance which canis familiaris eats which domestic dog. Equally information technology happens, the righteous Loyalists were eaten by the Communists and the righteous Falangists were eaten by the Nazis over the most decadent hole in Europe; so Miller was right.

Lawrence Durrell has said that the Tropic books were healthy while Céline and D. H. Lawrence were sick. Lawrence never escaped his puritanism and information technology is his heroic try that makes us accolade him. Céline is the typical European human of despair—why should he not despair, this Frenchman of the trenches of World War I? Nosotros are raising up a generation of young American Célines, I'm afraid, simply Miller's generation nevertheless had Whitman before its eyes and was non running back to the potholes and ash heaps of Europe. Miller is as skilful an antiquarian as anybody; in the medieval towns of France he goes wild with happiness; and he has written 1 of the all-time "travel books" on Hellenic republic ever done (the critics are unanimous about the Colossus of Maroussi); just to worship the "tradition" is to him the sheerest absurdity. Like almost Americans, he shares the view of the first Henry Ford that history is bunk. He cannot forgive his "Nordic" ancestors for the doctrines of righteousness and cleanliness. His people, he says, were painfully make clean: "Never once had they opened the door which leads to the soul; never once did they dream of taking a blind leap into the dark. After dinner the dishes were promptly washed and put in the closet; after the newspaper was read it was neatly folded and laid on a shelf; later the apparel were washed they were ironed and folded and then tucked away in the drawers. Everything was for tomorrow, only tomorrow never came. The nowadays was simply a bridge and on this bridge they are still groaning, as the earth groans, and non 1 idiot ever thinks of bravado up the bridge." As everyone knows, Cleanliness is the primary American manufacture. Miller is the most formidable anticleanliness poet since Walt Whitman, and his hatred of righteousness is also American, with the Americanism of Thoreau, Whitman, and Emma Goldman. Miller writes a skilful deal about cooking and vino drinking. Americans are the worst cooks in the world, outside of the British; and Americans are also neat drunkards who know nothing about wine. The Germanic-American Miller reintroduces expert food and decent vino into our literature. Ane of his funniest essays is about the American loaf of staff of life, the poisonous loaf of cleanliness wrapped in cellophane, the industry of which is a heavy industry like steel.

cantrellperep1987.blogspot.com

Source: https://onlinereadfreenovel.com/henry-miller/40698-tropic_of_cancer.html

0 Response to "Tropic of Cancer Henry Miller Read Online"

Publicar un comentario